Post-Op

Malcolm had passed his second full night “post-op.” He opened his lids and looked at us, with his bright eyes, as if he fully expected us to be right there and was saying, “Hey, I’m back.”

Our son looked positively pink, for the first time since his birth. Some minor bleeding into one of his lungs had stopped as mysteriously as it had started. The nurses were weaning him off the respirator. One hung a black-and-white mobile above his head and he stared at it, vigorously kicking his legs. They were beefy legs now, and his once-bony toes and fingers were pudgy. You might almost have been tempted to call him chubby! He was working hard to heal, the nurses told us.

Working hard. I looked down at my small son.

In his short life of five weeks, Malcolm had become, in my eyes at least, a hero. I couldn’t help but assign grown-up attributes to him—qualities like bravery, self-possession, and wisdom. He was only a baby, but he had endured more pain and trauma than many adults ever do—and he had survived with an uncanny, almost eerie stoicism.

I caught myself singing in the elevator on my way up to Malcolm’s floor. Bill and I felt so lucky. Malcolm was thriving. We had incredible support from our friends and families. My parents were keeping everybody updated on Malcolm’s progress—as well as looking out for Molly. They had even taken her to the vet to be spayed. In about a week, we would get back to Wakefield. Malcolm and Molly would finally meet, and the four of us would be able to take family walks.

The elevator doors slid open.

Suddenly, walking toward Malcolm’s unit, I heard the dreaded shrill alarm, signaling that a child was in a life-threatening state. It was a call to doctors to drop everything and come, as well as a warning to parents to get the hell out of there, fast. Emergency chest-openings could be done on the spot, in each small unit, but were closed to the public—and that included parents.

The heavy metal doors slammed shut in my face just as I arrived. I had no way of knowing if Malcolm was the baby in trouble. Parents who had been inside clustered around the doors. Lydia’s mom, one of my new acquaintances, rushed over to me.

“At least I know it’s not Lydia,” she said. “I was sitting beside her when the alarm sounded, and she was sleeping peacefully.”

“It could be Malcolm,” I said. “I just got here.” I cursed myself for having left briefly to try to sleep.

“Oh dear,” Lydia’s mom said. “Let’s sit down.” She led me to a bench and sat beside me. Lydia’s mom was Filipino, her husband American. Lydia was their teenage daughter, with beautiful Eurasian looks and a hole in her heart.

As a child, Lydia had undergone two successful cardiac procedures. She had one final surgery left and her parents, noticing that she was pale and tiring easily, had suggested she go ahead and have it. Lydia refused. Her parents insisted, wanting her to be in top form by the time she left for college, in less than a year.

It was a routine procedure, if you can ever call open-heart surgery routine. The operation went smoothly. But a few days later, as her mother described it, “Lydia’s system went berserk.” Her body ballooned with fluids; her beautifully sculpted face became round and bumpy. She broke out in a fierce systemic rash and suffered two major seizures. Having trouble breathing, she was back on the respirator.

“Her blood simply didn’t want to be rerouted in this new way,” Lydia’s mom had told me. That was her own personal analysis, and it was as good as anything the doctors could come up with.

Lydia’s case baffled everyone.

And Lydia, fully conscious and almost an adult, was furious with her parents for having insisted on the surgery.

“We just wanted to operate before she got too weak or sick,” Lydia’s mom had said. “And now I feel terrible.”

“You did the right thing,” I told her, clutching her hand.

“What else could you have done? She was failing.”

One of the huge doors opened and Cheryl, Malcolm’s new day nurse, came out. Cheryl was particularly fond of Malcolm. She’d told Bill that she had a dream about him. “He’s so handsome,” she said. She had nicknamed him “Hollywood Henderson” on account of his star quality and the breakthrough surgery. Now she was headed in my direction, her curly brown hair (that Malcolm loved to reach for), bobbing gently as she walked. I felt the blood draining from my face. Lydia’s mom squeezed my hand.

“It’s not Malcolm,” Cheryl said. “I knew you hadn’t been inside and I wanted to let you know.”

I exhaled deeply. Lydia’s mom wrapped her arm around my shoulder.

Cheryl walked over to a couple who had just arrived the night before. Their new-born daughter had been operated on in the middle of the night. Now they were both leaning against the wall by the elevators.

The rest of us looked down, not wanting to seem intrusive. Cheryl said something we couldn’t hear and the mother slumped against her husband. Cheryl helped the man hold his wife up. She said something else and he shook his head vehemently and said, “No.” His voice was loud and angry. He pressed the elevator button again and again. The doors opened and the two of them got on, the woman sobbing and pounding on the man’s chest. The shiny elevator doors closed.

No one moved or spoke. We all knew it could have been one of us.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter. On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event.

On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

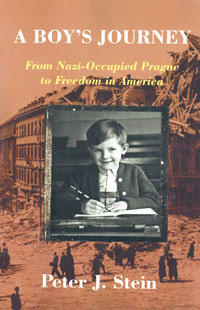

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event. This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America.

This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America. An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners.

An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners. Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry.

Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry. A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself.

A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself. This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod.

This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod. If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats.

If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats. The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices.

The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices. William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book.

William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book. Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.

Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.