Sweeping Away the Past

May 14, 2013

May 14, 2013

One of my cousins recently sent out a letter about our grandparents on my dad’s side, giving us some details from their lives.

None of us knew much about them. Dad was only 2 when “Frank,” my grandfather, disappeared without explanation. My father never saw him again. Grandmother would never discuss her estranged husband or her early life.

She would say: “Every generation should be swept clean,” in a tone indicating there was nothing more to say.

I find the concept troubling, that every generation should be swept clean. Isn’t knowing about our forebears worthwhile, important for the hoped-for evolution of human consciousness? Aren’t we supposed to learn from our family’s foibles and flaws as well as their triumphs?

A young friend of mine told me, “Being able to break away from the troubling behavior patterns in my family gives meaning and purpose to my life.” But how can we evolve if we don’t know what these patterns are?

Luckily, just before my grandmother died at age 95 (about 40 years ago), she relented and offered some spotty answers to the questions my cousin gently asked her.

I learned from his letter that my grandmother had grown up in the Irish neighborhood of Newark, N.J., and that her father was Irish, perhaps a drunk. My grandmother had kept this side of the family secret. Now she hinted to my cousin that she and her mother were apprehensive about the neighborhood bar on their corner. Had she found her father staggering in the street? We did know our grandmother was vehemently anti-alcohol all her life. But she never said why.

Ashamed of her rough Irish roots? Maybe so, but isn’t it important to share with one’s children the possibility that alcoholism might run in the family?

About our mysterious grandfather, my cousin found out that he was a recluse, deeply introverted. “He had a workroom on the third floor, and was almost always there. He didn’t join in on family activities downstairs.” I learned from the letter that my grandfather had been a draftsman and an inventor. He collected newspapers, magazines, buckets of random keys. Pencils. Was he also a hoarder?

“One day they went up to his workroom,” the letter continued. “He was gone and everything of his with him. Where he went at the time is not known, but it was not possible for the family to locate him.”

So many questions: What triggered his leaving? Did Grandmother ever try to find her him? Not a word about that.

All we know is that the couple never divorced and Grandfather never again saw three of his four sons. For decades, according to our cousin, Dad believed his father was dead, his mother’s silence on the subject was that profound.

When my 85-year-old grandfather lay dying in a Newark hospital, my one uncle who had kept in touch with him encouraged my dad to visit, but Dad wouldn’t go. Like his own mother, my father didn’t want to talk about or face hard things.

Oprah Winfrey and others have said that we’re only as sick as our secrets, and I agree. What my grandmother didn’t seem to appreciate is that we pass on volumes to the next generation, whether we want to or not. Through osmosis, our parents’ prejudices, shame, and fear enter us and take up residence. Feelings that are stuck in our unconscious leach out in our behavior, shape our relationships and worldview.

The burden of secrecy rarely stops with a single generation. I bore it too, from an early age keeping much of my life secret from my dad. My father never knew, for example, that he, my mother and I existed in a tangled and treacherous triangle, that all my life Mother shared with me her darkest worries and sorrows about him, about their marriage, his career, his unfaithfulness, but swore me to secrecy.

There is no sweeping clean. Only through revelation and candor can we begin to illuminate and release what keeps us, and those who come after us, in frozen pain and ignorance.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter. On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event.

On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event. This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America.

This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America. An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners.

An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners. Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry.

Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry. A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself.

A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself. This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod.

This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod. If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats.

If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats. The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices.

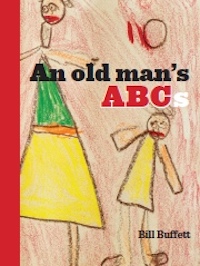

The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices. William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book.

William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book. Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.

Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.