Tea with Mrs. Bennett

I lay on my old bed, in my childhood room, Molly curled up at my feet. Cold sleet blew in sheets across the yard, pummeling the storm windows. The weather was too nasty for walking.

Bill had taken the commuter train into New York. I was supposed to have gone with him for a lunch with my erstwhile boss, but try as I might, I hadn’t been able to pull myself together to make the trip. Let’s face it—I just wasn’t the Jackie Kennedy type, to preside heroically and regally over public tragedy. All I wanted was to spend my days walking in the woods. The natural palette of the wintry landscape soothed me—brown leaves, black tree trunks, an occasional burst of green fern or moss, a tangle of eggplant-colored vines. . . and the slate-gray sky. Most of the vegetation was dead or dormant and I felt comfortable in its presence. Being cloistered indoors made me think about the mundane, painful tasks that lay ahead.

We had to go back to Wakefield and deal with the gifts that had arrived for Malcolm. I hadn’t even had the heart to open them all yet. What would I do with everything? And every day, the mailman delivered a stack of condolence notes to my parents and to Bill and me. I knew a fresh mound of correspondence would be accumulating under the mail slot in Wakefield. We had to finish fixing up the place, sell it, pack it up, and move. We had to find an apartment in Boston. I had to find a new job. Thinking these thoughts made me cold. I pulled another blanket over Molly and me. In a book I read on grief, the author said the bereaved should never move right away, that there was no way to escape the pain. You couldn’t leave it behind—at the last house, in another state, in another country. Grief followed you wherever you went.

But we had no reason to stay. We had no long-standing friends in Rhode Island; we felt no sense of community, had no history in the place. The only good that had come out of our brief stay was Molly.

If I’d written that book, I would have advised people not to move while pregnant—or if you must, to rent, not buy. Then, if your baby dies, you can get out of the deal easier. I’d also tell people to avoid the freelance commuting life, with no built-in professional ties to your new community. I’d say: move to a place where you have lots of friends and emotional support. . . in case your baby dies.

But who ever expects their baby to die?

An article on grief warned that a high percentage of couples who lost children broke up after the tragedy. Bereavement was tough on couples who needed to share every experience or who were threatened or angered if their spouse didn’t see the experience exactly the way they did. There were examples: A woman accused her husband of being unfeeling because he went to work while she stayed home, unable to think about anything but their dead daughter. It was boorish and insensitive of him to work, she claimed, and she hated him for it. But for him work brought distraction—temporary relief from the pain. She resented his finding any solace when she could find none. And he resented her accusations that he lacked feeling.

I thought about the fisherman’s wife who had had to hide all her feelings from her husband—one tear would send him into a rage. I could scream and cry with Bill—I could say anything. He wasn’t frightened by my grief. I was more scared of it than he was.

In any case, it was decided: we were going to move. And I knew we weren’t going to split up, even though our responses to Malcolm’s death had been, would continue to be, completely different. I was the one who had carried Malcolm those nine months. I had borne him, fed him, and cared for him constantly. Bill had been involved too, but we both knew he hadn’t felt the same bond—and that was all right; it was natural. I didn’t hold it against him for not feeling the loss as intensely as I did. And I was grateful he was able to work—after all, somebody had to pay the bills!

Once we had moved to Boston I would have to look for work. I sighed. How was I going to do all these things when I barely had the energy to drag myself out of my bed in the morning? Having always been a nervous type, a busy person who feared idleness, I was frightened by my leaden despondency. I had to get up. I had to do something with myself. I rearranged my feet around Molly. She began to pant slowly and hopped down from the bed, curling herself into a ball before settling beside me on the floor. I had to get a life. I closed my eyes—longing for a dreamless sleep that wouldn’t come.

Mother tapped softly on my door and came in. A neighbor of hers, Mrs. Bennett, whose husband had died recently, wanted to come see me.

“I told her she could come for a cup of tea after lunch.”

“You what?” I asked. I barely knew this woman, hadn’t seen her in years. Had she even come to our wedding? I couldn’t remember; Mother had invited dozens of her friends, people I barely knew. Mrs. Bennett was a frail southern lady who had always seemed ancient to me, even though she had a daughter several years younger than I was. Her husband, a judge, had died recently. Growing up, I had barely known any of the Bennetts. The daughter, Lisa, had gone to private school in town—or perhaps it had been boarding school somewhere, I couldn’t remember. I never saw her and I’d never been in their house. The only member of the family I was acquainted with was their black lab, Tarzan, who used to comb the neighborhood in those days, looking for garbage.

“I would barely recognize the woman,” I protested. “Why are you letting her come see me?”

“She insisted,” Mother said. “I don’t know why.”

All morning my stomach tossed at the thought of the impending visit. Of all people in the world, why would a near-stranger like Mrs. Bennett be coming? Aside from my sisters, my parents, and my husband, I wasn’t seeing anyone. I hadn’t even called any friends in the ten days I’d been at my parents’ house. When people called me, Bill handled them. How was I supposed to get through this visit without having a complete meltdown, a grief attack like the one I’d had in church? That time, as Mother maneuvered me out of the chapel, I’d been sobbing hysterically—and mortified by my public display. I’m sure she was too. Luckily we hadn’t run into any of her friends on the way to the car. But now, Mrs. Bennett was coming.

Despite the rotten weather, I took Molly for a short walk around the block. We passed Mrs. Bennett’s house. What was she doing in there? What was she planning? I almost hoped some kind of minor tragedy would intervene before lunch, that she would slip and sprain an ankle—get an emergency phone call from Lisa and have to leave town immediately.

As the noon hour approached, my dread thickened. I couldn’t eat lunch. What if Malcolm started crying in my ear while Mrs. Bennett was sitting beside me on the couch? What if hospital images flooded my brain? What if I started screaming?

The doorbell rang. I heard mother and Mrs. Bennett chatting in high-pitched tones in the front hall. I had changed out of my sweat clothes—my indoor/outdoor outfit—into a skirt and sweater. The waistband rubbed my still-puffy belly, but at least I didn’t look like I had just had a baby or was about to deliver. I sat on the bed in my room, furious at myself for not having gone to New York with Bill.

Mother called for me. What could I do? Have a sudden attack of “the vapors” like my grandmother? She had had one just before my mother’s wedding—and couldn’t attend. No, I had to go down. My knees were shaking as I descended. Could Mrs. Bennett tell?

“Hello, dear,” she said, tipping her head to one side to get a better look at my lowered eyes.Her face was porcelain-perfect with make-up; her lips bright red. She had recently been to the beauty shop for one of those puffy Princeton-lady hairdos. I could see through her curly frosted hair to her scalp.

“What a pretty skirt,” she said.

“Thank you, Mrs. Bennett,” I said, shaking her small, lotioned hand. My voice faltered. Oh no! Was I going to collapse, right there in the front hall? But Mrs. Bennett, paying no attention to my crumbling tone, chattered on, like the Mrs. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, about the lovely slipcovers, “Were they new?” and the dreadful weather.

Mother led us onto the sunporch and disappeared to make the tea. I could have killed her for abandoning me. Molly sat at my feet, like a seeing-eye dog.

Silence. Some people thought a momentary silence in a room signaled that an angel was passing by. I was embarrassed by silence—it just represented one more social failing. I hoped Mrs. Bennett believed in angels.

She gazed at me and smiled. Please, I begged silently, don’t let her say something sympathetic that makes me lose it in front of her. I looked down again, feeling hot tears in my eyes. I wanted to dash outside and run all the way to the woods.

“Tell me about Molly” she said. “How old is she?”

“She’s seven months,” I responded, wishing I were holding Malcolm in my arms and she was asking me how old he was. My lip trembled. I pushed the thought and the tears away.

Mrs. Bennett nodded and smiled. “Where did you get her?” she asked. Her penciled eyebrows went up, like French accent marks.

“I saw an ad in the paper,” I said, “when we were house-hunting.”

Oh god, I thought. She’d better not ask me about our house. I knew I couldn’t talk about that.

She didn’t. She asked me what I knew about Molly’s family.

I told her about Molly’s mother, how the ad in the paper had said she was such a good retriever she could carry an egg in her mouth without breaking it. The words jerked out of my mouth. I felt out of control, but at least I wasn’t sobbing.

I remembered her dog, Tarzan, the black lab, and asked her about him—and then I realized, before she could speak, that he must be dead by now. I hoped she wouldn’t say something about his being gone. That would definitely set me off.

“Oh, that wanderin’ man,” she said, with a laugh. “He was always out stirring up trouble. I often said if he’d been a man he’d have made a wicked politician.”

Silence. Another angel. Another social gaffe. I couldn’t think of anything to say, anything at all!

I crossed my ankles and wished I could disappear through a trap door in the couch, deus ex machina. Mrs. Bennett’s eyes were on me; I could feel them.

“Well,” she said, sighing, “the weather certainly is wicked, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is,” I said, shaking my head.

As though satisfied I had said enough, Mrs. Bennett took over the conversation. She told me about her daughter’s recent trip to Europe. She complained some more about the weather. Mother appeared with the tea and then left again. Damn! Mrs. Bennett talked about the delicious tea, “so good with lemon.” My throat was lumpy, but I was able to keep my mind on what Mrs. Bennett was saying.

We sipped tea. Finally mother returned for good. The two of them chatted. I thought about people I knew who could discuss scary and upsetting personal matters without showing any emotion. How did they do it? I had absolutely no social persona and no willpower, none at all.

“Well, I’d best be getting home,” Mrs. Bennett said. We all stood up and walked to the front hall. Mother fetched Mrs. Bennett’s coat and umbrella from the closet. On her way out the door, Mrs. Bennett turned and grabbed my hand.

“There,” she said. “You did it.”

And she was gone.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter.

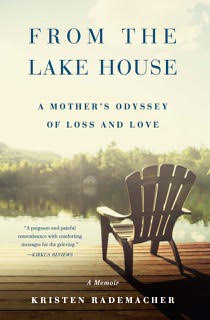

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter. On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event.

On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

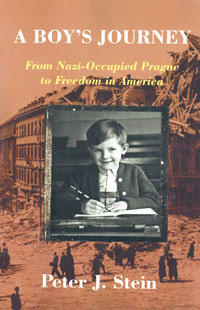

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event. This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America.

This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America. An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners.

An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners. Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry.

Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry. A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself.

A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself. This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod.

This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod. If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats.

If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats. The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices.

The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices. William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book.

William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book. Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.

Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.