Epilogue

“When the pupil is ready, the teacher will come.”

– Buddhist saying

On a drizzly December morning, my neighbor Gail and I stood solemnly in my back yard. She placed a small bouquetof rosemary and “the last mums from my garden” on the freshly turned mound of earth. Molly, age ten, had died the day before.

“She was considerate right up to the end,” Gail said.

It was true. We had not had to look on, helpless, as Molly became demented, incontinent, or gimpy with arthritis. She never did hard time in an Intensive Care Unit, attached to tubes and monitors. When she died, she was a lumpier, grayer version of her youthful self, but still reasonably fit.

And she spared us that torment every pet owner dreads—we didn’t have to have her “put down,” and be haunted, for years, by our decision.

Even in her death, Molly was gracious, quick about it: Sick on Sunday. An inconclusive trip to the vet on Tuesday. “Bring her back in a few days for blood work if she doesn’t improve.” Dead on Wednesday.

The morning she died, I had put our daughters on the school bus and taken Molly for our daily walk in the woods behind our house. I threw a stick for her. She ambled off the path, tail wagging, and gingerly sniffed out her prize. As always, she carried it proudly back to the house.

I thought she was getting better. After throwing a few tennis balls for her, I left her in the back yard to sun herself in her favorite spot.

Minutes later, I went out to check on Molly.

“Come on in, girl,” I said, thinking she’d be ready for her morning nap in our bedroom. But now, she was lying flat on her side. She managed to pick her head up and look up at me with her doleful eyes, then instead of rising, she lay down again, her head on the ground. It was the first time in ten years she hadn’t come when I’d called her.

I rushed to her, knelt down and cradled her head in my arms. She was breathing heavily, a line of foam forming on her black lips. I looked at her gums. They were gray, the color of death.

I yelled for Bill. “She’s bad,” I said. “She’s dying.”

“I’ll call the vet,” he said. “Maybe she’s had a stroke.” He rushed back into the house.

I sat cross-legged on the damp ground and gathered Molly’s sixty-five pounds onto my lap. I stroked my favorite part of her, the shiny black fur around her shoulders.

“You’re the best dog ever,” I said. She looked me right in the eye—a wistful stare. I looked back, trying not to cry. She had always been there for me; now it was my turn to be strong for her.

“It’s okay,” I said. “You can go.” Molly turned her head away, and I felt the life shudder out of her.

I just sat there, I don’t know how long, with my dead dog in my lap. I watched the squirrels, always reluctant when Molly was outside, dart across the yard with a new boldness. Already they knew.

Molly had been present for so much—the three moves in one year, the buying and selling of two houses, our move to North Carolina to live in the house Bill had grown up in. She was a stalwart playmate for our daughters, even through their tail-pulling toddler years. On sidewalks and beaches, through woods and fields, Molly and I had logged hundreds of miles together. More than any other living creature, Molly had been my companion in grief. As my mother later put it, “Molly was your best friend.”

I was grateful to be able to hold her while she died. If only we could all go this way—in the arms of a lifelong friend, after a morning walk.

One death brings up all the others. I thought about Malcolm’s. If only I could have held him like that while he died. I had a chance to hold his body in the hospital chapel afterwards, but I had fled

I hadn’t known anything then—about loss or grief. I was a novice, uninitiated. Back then, I wouldn’t have wanted to hold him while he died. Even the thought of it would have been abhorrent to me.

How I had changed.

As I sat feeling Molly’s heavy dead weight in my lap, I rescripted Malcolm’s death, thought about how I might have handled it now, so many years later. I could have said to Dr. Casteneda: “No more.” (I knew there was no real hope, even enthusiasm, for the second surgery. Everyone knew.) I could have told the doctors to unhook Malcolm from those useless machines and painful needles. I could have said, “I’m taking him home to die in peace.”

At home, I would have bathed him, dressed him in a tiny outfit, and wrapped him in a blanket. I would have rocked him and sung to him and told him how much I loved him—until he died.

Now, I would do those things. Back then? I couldn’t. I didn’t know how. I lacked the ability even to imagine such actions.

Not visiting Malcolm’s body was one of the most naive acts of my life. But, I had forgiven myself. Before I lost Malcolm, my mission had been to push away, to try to bury the dark, unconscious, scary aspects of life. After Malcolm died, I had no choice but to sink headfirst into the very wasteland I had tried desperately to sidestep. Yet, as one recovering drug addict has written, it is in that terrifying state of nothingness and loss that one often first sees the “dark face of wholeness.”

What is life, after all, without death? Light without darkness. Joy without sorrow. Searching for a sanitized happiness was no longer my goal. Nor was coveting the lives of others.

The task was to seek meaning, to deepen my own inner experience, to live in the present moment, and to try to be a beacon to others in need.

As I felt the dark ache of grief for Molly sweeping over me, I knew there was no way to avoid the pain. And even though she was only a dog, I knew I would spend years coming to terms with losing her as well. Grief, I know now, has its own mysterious timetable.

Bill and I dug a deep hole in the backyard, under a dogwood tree, near the spot where Bill’s childhood dog Duff was buried, along with my sister Nancy’s dog, Daisy, who had died when they were visiting us one Christmas. Tasha, our back-up dog, would not be buried in our yard. We had given her to a cousin in California, who was going through a wrenching divorce and had fallen in love with Tasha on a visit with us. In her new home, Tasha had no young children to snap at and no other dogs to compete with. Now, with Molly’s death, we were dogless.

When the girls came home from school, I told them right away about Molly. Colette, who was six, put her arm around me and said: “Just think, Mama, now Malcolm can throw cloud balls for Molly to catch up in heaven.” Olivia went to her room, to grieve alone. Her mother’s daughter, I thought. When Olivia had turned five, Bill and I told her about Malcolm’s brief life. She was old enough to ask the hard questions we had dreaded: Why did he have to die? Where was his spirit? Instead, she skipped away to open the door for the cat, who had appeared outside, as if on cue.

But the next morning I found her slumped over a bowl of Cheerios at the breakfast table. She looked up at me and said, “Just because I never knew my brother, it doesn’t mean I don’t miss him. I wish he was sitting here beside me having breakfast.”

For Olivia, the story of Malcolm had just begun.

Bill and I vowed our daughters wouldn’t grow up shielded from death, as I had. They have seen the bodies of dead relatives, been to funerals, and talked freely to their parents about the meaning of life and death.

When Rosie, our pound mutt, was hit by a car, Bill and I took the girls and our other dog, Daphne, to the vet’s office to hug her lifeless body and say our good-byes. Later, we drew pictures of Rosie and made a list of her most lovable qualities.

That night, the woman whose car had hit Rosie, made a courageous surprise visit, bringing us flowers and a note expressing, “my deep sympathy for your loss.” A random stranger, she had not only stopped her car to inform us she had hit our dog, she also phoned the vet later to find out if Rosie had made it.

She was not an innocent, I said to myself. She was someone who had been there. I thought of all the condolence notes I hadn’t written, all the suffering folks I had shunned, all the deaths I had shuddered at and turned my back on. But that was before—before Malcolm.Every year I am aware of Malcolm’s birthday. I always wake up on September 22nd thinking about him, missing him, wishing he were present. For ten years, I couldn’t get through a single birthday without crying. Some fleeting moment would inevitably trigger me—a few phrases of melancholy classical music heard on the car radio, a lanky boy about the right age pedaling by the house on a bicycle, my mother’s phone call just to let me know she too was thinking of Malcolm—even if we didn’t mention him.

Several years after Malcolm’s death, after we had moved away from Boston, I contacted the other grieving women I had met and asked them how their feelings had changed over the years. Greta, who has a healthy son, said: “You go shopping and find yourself looking at the clothes for your dead child’s age group.” Debby now has two sons, close in age to my daughters: “There’s always a sense, somehow, that someone is missing,” she said. After Carolyn, Dot had had a healthy daughter: “I never know when it will hit me. At my oldest daughter’s school graduation, I suddenly broke down. Carolyn would never graduate from anything.”

We all agreed that the best thing we had done for ourselves was to seek out Cathy Romeo—and each other.

Do I think about Malcolm often? Yes, just about every day. Do I find myself conjuring up a phantom son—a boy, tall like Olivia, with piercing blue eyes like Colette’s? Not often. But I keep track of the big events he’s missing—going away to camp, becoming a teenager, graduating from middle school, getting his driver’s license. I can’t help myself. I am still a mother who counts. And I am still a mother who cries, when I least expect to.

It happened at the Driver License Office the other day. Having just passed the eye test without my glasses, I was ecstatic. Never mind that I’d had to ask the examiner if the hieroglyphs I was squinting at were letters or numbers. The good news was that, when my glasses were lost, I’d still be able to drive, legally. All I had to do now was get my picture taken and leave. The entire ordeal had taken less than twenty minutes. I wouldn’t even be late to work!

“You’re up next,” the examiner said. “Right after I photograph this young man.” I glanced at the boy—clad in jeans, a white T-shirt, and oversized basketball sneakers.

He ran his fingers through his mop of disheveled dirty-blond hair; his father gave him a proud clap on the back. The boy beamed up at the camera, triumphant. He was sixteen and getting his first license.

Something about that boy triggered everything. My mood plummeted. In a flash the everyday world shattered, and I entered another reality, a timeless zone of deep, frantic pain.

Malcolm would have turned sixteen this fall.

Pallid in front of the camera, I faked a smile for the driver’s license examiner. This too will pass, I told myself . . . until next time.

Every summer we return to Rhode Island for vacation. Sometimes we stay in our old house in Wakefield. My parents now have retired there full-time. They’ve completely remodeled the upstairs. Malcolm’s room has been merged with the adjoining bedroom and so no longer exists.

But the red maple is still there, in full glory, out the window. Sometimes, I look out and remember everything vividly—the sleepless nights, Malcolm’s grunting, my sweaty terror. Other times, what I’m seeing is only a regal tree I’d like to climb. At the beach on sparkling days, I sometimes stand by the ocean’s edge, in the spot where we scattered Malcolm’s ashes. I gaze out at the razor-line horizon. I feel the play of the cool waves around my feet, the salty mist on my face, and the sun on my body. I’m glad we chose to cast our son’s ashes into that magnificent sea. At the water’s edge, I close my eyes and wait for the enduring image to appear. It materializes on the inside of my eyelids, the image of Malcolm and me looking out at the view together, our silhouettes etched like bronze pennies. As long as I am of clear mind, I will find peace in that picture. And as I grow older, the image becomes sweeter and stronger. The wrenching memories recede. Like old newsprint, they are fading, becoming harder to read.

Malcolm and I stand together, gazing at the tranquil view. Our silhouettes are strong—mother and son, together. Always. We are bathed in radiant light. And love.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter.

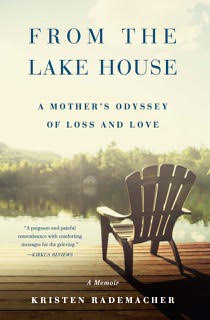

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter. On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event.

On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

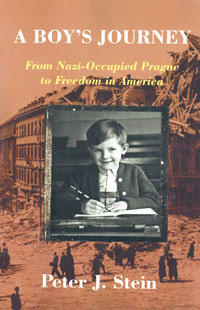

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event. This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America.

This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America. An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners.

An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners. Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry.

Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry. A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself.

A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself. This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod.

This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod. If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats.

If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats. The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices.

The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices. William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book.

William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book. Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.

Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.