My Father’s Stories

December 21, 2011

December 21, 2011

I’m heading off to visit my father in Philadelphia, a pilgrimage I don’t make often enough.

These trips are exhausting though nothing much happens. Like an old dog, my 93-year-old dad sleeps – a lot. When he’s awake and has something to say, his voice is barely a whisper and his thoughts come out muddled.

But I’m hopeful this time. I’ve got something that just might jumpstart a coherent memory bank.

Let me explain. When he called recently (my sister did the dialing) the conversation began the way it usually does.

“I’m so glad to hear your voice, Daddy,” I said.

He mumbled something I couldn’t understand.

Instead of saying, “What?” I’ve learned to move on, to tell him something, anything. That day I picked up the book I was reading, “Unbroken: A World War ll Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption,” by Laura Hillenbrand. It’s about an American POW named Louie Zamperini, who, like my dad, was a track star and served in the Pacific.

“Dad,” I said. “Did you know a guy named Louie Zamperini when you were training out in California?”

“Louie,” my dad said, his voice suddenly crisp and loud. “Of course. We ran together.”

“And he served in the Pacific during the war Dad.”

“I know. I remember him. He was shot down. Survived in the water for weeks.”

Delighted by my father’s clarity, I named some Pacific islands from a map in the book. My father volunteered others.

He faded again, but at least synapses had fired.

When I visit I usually wheel Dad around the gardens of his retirement community. He’ll perk up at the names of flowers and trees and he enjoys listening to the birdcalls. My father was an avid gardener, an Olympic qualifying runner, a Princeton graduate, a WWII veteran, the father of three girls, and an unfulfilled public relations man. He’s been a widower for almost a year.

On this trip, it’s going to be cold and gray, probably not garden-gazing weather. He’ll want me to park him in front of the television by the nurses’ station.

“No, no!” he’ll say, sometimes shouting it, if I try to take him to his room so we can “talk.” He’d rather watch “Jeopardy,” old movies, sitcoms, cooking shows, whatever. Ironic for a man who forbade television, and insisted on family conversation, when his daughters were young.

This time, with “Unbroken,” I just might be able to lure him into his room, a lovely space with a portrait of his late wife, familiar furniture from my childhood, and lush plants.

My dad had served on the staff of Admiral Nimitz, whose title was Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. I now have a large photograph of the admiral – it used to hang in my father’s office – with an inscription by his boss, the admiral, thanking my father for his WWII service.

“Dad,” I’ll say. “Louie was also honored by Admiral Nimitz.”

Growing up, I paid little attention to the sagas my father told at dinner. I watched the candles burn and tried to remember to keep my elbows off the table. If I didn’t he would poke them with his fork, and it hurt. I would wait, stony faced, until all the plates were cleared and I felt safe to ask: “May I please be excused?” His answer wasn’t always “yes.”

Now all these decades later, I’m going to read to him from “Unbroken.” Hopeful he’ll remember some of his tales and tell me again. I want to hear what I was too scared and distracted to listen to when I was a little girl – those stories I never knew I’d want, some day, to know.

When I arrive he has just come out of the bath and I’m able to wheel him to his room without protest. I pull a chair up beside him and thumb through the book, showing him the accompanying photos and reading an occasional paragraph.

“POW’s, yes, there was Frank and …” he waves his arm, searching for more names. Other tidbits follow.

Then I read my dad the two-page preface. His face squishes up, his mouth turns down, and he begins to sob. He can’t stop.

“I’m sorry, Daddy,” I say. He places his long bony hands over the open book as though it were a sacred tome. His head nods up and down.

“Should I continue?”

“Yes,” he whispers. No more words come from him, but as I read he grabs my hand and squeezes, his head bobbing with recognition.

It is my turn now to tell him his story.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter. On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event.

On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event. This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America.

This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America. An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners.

An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners. Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry.

Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry. A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself.

A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself. This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod.

This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod. If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats.

If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats. The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices.

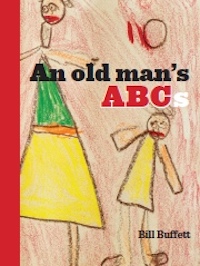

The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices. William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book.

William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book. Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.

Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.