Dog Woman

Dr. Patty Romph looked at me and smiled. Her eyes reminded me of a Labrador retriever’s—sad, with puffy, down-turning brows. As she came towards me, I could smell the out-of-doors on her, a loamy and slightly salty odor. I realized that, for the first time in my life, I hadn’t breathed any fresh air for three whole days.

She held out a large, red, chapped hand, one that had obviously worked a spade, hauled rocks, and pulled weeds.

“Sorry it took me so long to get here. I came as fast as I could.”

She was a tall, almost gawky woman, with long wavy brown hair flecked with gray; some of it had been pulled back, sloppily, into a barrette. She wore no make up. I guessed she was in her mid-forties. Under her buttoned lab coat, I could see corduroy pants, and she was wearing muddy lace-up leather boots with rubber bottoms, like the kind advertised in the L.L. Bean catalog.

“One of my dogs got caught in a trap this morning,” she explained. That was why she was muddy—and late.

“May I?” she asked, reaching for Malcolm. She gathered him into her arms, as though he were rare Chinese porcelain, and laid him carefully in his isolette. She swept her hair back and hunched over him, her stethoscope searching his tiny chest for clues.

There had been absolutely no reason to suspect anything would be wrong with my baby. At twenty-nine I was robust, with sinewy muscles. I had recently quit dancing, but my ten-year career as a modern dancer had kept my body trim and flexible. Always a tomboy, I still relished an impromptu game of touch football and a good climbing tree. People said my stride was like my father’s, and he had been a track star in college. I had inherited my dad’s iron constitution. He never got sick; neither did I. I had the boundless energy of an adolescent dog. Bill was healthy too. He suffered from occasional headaches, but they were never so severe that a few crushed aspirin in water wouldn’t cure them.

Dr. Romph turned Malcolm onto his stomach and listened to his back. She shook her head slightly and held back a moment before she spoke. “I’m afraid Malcolm’s a very sick baby,” she said finally, straightening up and slipping her stethoscope into her lab-coat pocket. She picked him up and held him in her arms. “I can’t tell from listening what’s wrong with his heart, but it’s definitely not pumping efficiently.” She looked down at him with a tender, almost forlorn expression. “We need to get him on some medications right away and try to stabilize him, see how he responds. And we’ll have to transfer him to a bigger hospital. Today.”

I couldn’t speak.

She handed Malcolm back to me and sat down in a chair next to my bed. How different she was from the last doctor, from any doctor I had ever encountered.

“I know this is very hard for you,” she said. “And I’m so sorry.”

I felt the corners of my mouth pull down, and a lump, like a pressing thumb, in my throat. But no tears came.

She asked if there was heart disease in my family or Bill’s. Normally, I wouldn’t even consider illness and my family in the same breath. We were healthy people. On my side, they seemed almost to disapprove of illness, scorning infirmities as though they were moral weaknesses or signs of a lack of will. Being ill was like being fat or lazy, a condition one should be able to control. Illnesses happened to other people in other familiesÑnot to industrious, sturdy types like us. I shook my head.

“Do you remember being sick any time during your pregnancy?”

“No.” I said. “Wait. I think I had some kind of the flu early on.”

“Really? How early?”

“I’m not sure right now.” My head was throbbing and I felt panicky.

Dr. Romph pressed my arm gently. She told me she had to make a few phone calls but that she’d be right back. “Will you be all right while I’m gone?”

I nodded. Before leaving the room, she gently pushed the box of tissues on my tray table closer to me.

“Try not to think about it,” my mother had always advised me, whenever something unpleasant threatened to happen or, God forbid, did happen. We were the prototypical American family of the 50s and early 60s: we didn’t discuss scary and painful feelings in our household. Denial was our modus operandi.

And I did try hard not to think about bad things. But any scary TV movie, glimpsed surreptitiously at my friend Tracey’s house, could disturb my sleep patterns for months with horrific bad dreams that haunted my waking hours. No one suspected my torment because I had learned to keep it to myself. Unspoken, my fears thrived.

Being a dancer and an athlete, I knew and trusted my body—on the outside. But I worried constantly about its hidden, intracellular workings and about the possibility of illness or grief or death bursting into my life. Now, all my dread fulfilled, how was I supposed to think about anything other than the fact that my beautiful pale son, lying there in my arms, was critically ill.

I put Malcolm down on the bed beside me and reached for my journal. Although “diary” hadn’t been on the Lamaze teacher’s list of items to take to the hospital (along with toothbrush, nightie, etc.), I had brought mine with me. I took it almost everywhere, even sometimes to movies so I could scribble down good dialogue, in the dark. Early on, I had learned that just to record a slice of my life—a snatch of overheard conversation, a fear, a dream—created a helpful distance between me and my immediate experience. Once an image had been written down, it didn’t wield quite so much power over me.

I turned to the first blank page of my journal and wrote, “‘I’m afraid Malcolm’s a very sick baby,” Dr. Romph said.”I stared at the page. Before writing more, I realized, I would have to locate an earlier entry.

Thumbing through the dog-eared pages, I found what I was looking for—a conversation with my first OB-GYN, Dr. Harper, in New York, hastily scrawled while I was supposed to be getting dressed after the exam:

“One last thing!” He’s leaving the room. It is now or never.

“Yes?”

“I was sick in the first few weeks.”

“Morning sickness?”

“No. I think I had the flu or something.”

“Your symptoms?”

“I was achy and had chills and bad swollen glands.”

“Any fever?”

“Yeah.”

“How high?”

“It got up there. Once it was 103.”

“Did you take anything?”

“No, but I soaked in tepid baths . . .”

“Don’t worry,” he says. “Lots of women catch colds during pregnancy and deliver healthy babies. You’re healthy and strong. I’m sure you’ll do just fine.” And then he’s gone…

I’m giddy with relief and proud of myself for telling him about the high fever. For once, I didn’t downplay my concern, make light of a situation I secretly took most seriously. The trouble is, I’m afraid of facts. If they aren’t delivered in just the right way, I can put my own twisted spin on them, skew them to ignite my paranoia.

The buzzing clock roared in my ears. I wondered what Dr. Romph was saying now to the people at Rhode Island Hospital. I didn’t want to think about it. I turned back several pages and read more journal entries:

Dream: In my seventh month, I give birth prematurely to a golden retriever or maybe it’s an Irish setter. The dog, named Dawn, is amazingly smart. When she’s one day old, she already knows commands, like sit, lie down, roll over. She’s big, almost full-grown, in only a few weeks. I feel guilty for wishing she were a baby and not a dog.

Do other pregnant women have such idiotic dreams?

Dream: Twelve little boys have been sliced down the middle of their chests. A man arrives who can mend the dead infants. We are struggling against a horrific queen who rules the land, but she is taking her daily swim in the dark lake now so we must make sure the man works fast to cure the little boys, before she returns.

Was it possible these dreams had been trying to tell me something was wrong with my child? Dr. Romph came back into the room. I closed my diary, slid it under the covers, and picked Malcolm up again. He felt like a damp rag doll, except that he was breathing very quickly.

I told her about the flu and my talk with Dr. Harper. She told me she too thought warm baths were curative. I marveled at this—a doctor saying she believed in something as folksy as soaking in lukewarm water. My mother, who swore by the healing powers of witch hazel, Epsom salts, Vitamin C, and spirits of ammonia, would love this woman.

Dr. Romph asked me where I lived and somehow our new puppy, Molly, came up in the conversation. She seemed interested in everything about my dog, even wanting to know the colors of the other pups in the litter and how we had house-broken Molly.

“I have Samoyeds,” she said. “And they keep me busy.”

She had a soft, almost muted voice. Maybe it was her hushed quality that made me think she had a melancholic streak. I sensed that she didn’t have children, that her dogs were her children. I wondered if she was married, but didn’t ask.

Bill walked in with his mother, straight from the railroad station. They both looked pale and slit-lipped.

As Dr. Romph introduced herself, Bill’s shoulders relaxed a notch and his jaw bones loosened their clamp on his teeth. I could see her quiet manner reassured him. She stood back while Bill’s mom, Nancy, admired Malcolm.

“He looks just like Bill did as a baby,” she said, her voice tentative. I could tell my mother-in-law was shocked. Clearly, this wasn’t the joyous meeting she had so eagerly anticipated.

Malcolm would need to ride in an ambulance to Rhode Island Hospital. They would start him on an IV and medicines before he left. At the hospital there were places where we could sleep. Patty Romph removed my cesarean stitches, so we wouldn’t have to think about them later, and arranged to have me discharged—immediately.

How could I have complained, earlier in the morning, about the dismal hospital bed? Now I wanted nothing more than to stay in it, with my baby in my arms.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

I'm happy to be part of this collection of personal stories, a collaboration involving over 60 teachers of memoir from around the world. The book is published independently by the Birren Center for Autobiographical Writing, through which the authors are certified to teach.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter.

A unique and beautiful exploration of Helen Keller's abiding friendship with prominent journalist Ed Chamberlin–and much more about Keller's struggles, passions, and values. The author is Chamberiin's great-great-granddaughter. On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event.

On August 8, 2020, in pandemic heat, I introduced Kristen Rademacher (via Zoom)at the launch party for From the Lake

House, A Mother’s Odyssey of Loss and Love, her wrenching memoir. Flyleaf Books, our hopping indie bookstore here in Chapel Hill, NC, hosted the event. A large crowd from across the country and around the world tuned in for the inspiring multi-media event. This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America.

This poignant memoir gives a boy's view of life in Nazi-held Prague and his escape to freedom in a challenging America. An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners.

An award winning collection of powerful stories about serving the many needs of elderly and indigent patients, as one of America's first gerontological nurse practitioners. Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry.

Essays by women ministers about their challenges and victories in answering the call to ministry. A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself.

A mother's 40-year struggle to raise an autistic son – and to grow up herself. This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod.

This idyllic memoir recollects the sweet and simple summer pleasures of family life in mid-century Cape Cod. If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats.

If you love your pets and make sacrifices for them, you will adore this lively book about a family's needy cats. The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices.

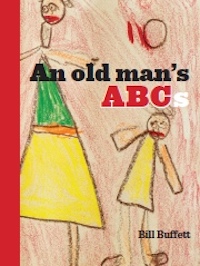

The history of a women's shelter in Birmingham, Alabama, as told through many voices. William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book.

William Buffett's short essays on nearly everything, arranged as an alphabet book. Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.

Essays about one man's dimensional life including some of his favorite recipes.